That the first Niners-Rams meeting ended in a tie was a surprise – the first tie in the NFL since 2008. But that the second meeting almost ended in a tie too…well, that’s just nearly unbelievable.

But that’s what happened!

And that’s why we love the NFL. Best reality TV on TV.

Thankfully, Greg the Leg won the game for the Rams with thirty seconds left in overtime and prevented general mayhem from erupting in the NFC West.

The Niners helped the Rams score two points on their way to the eventual overtime victory. Let’s define a few things and then get into what happened.

The Rams earned their first two points of the game off of a safety scored due to a penalty for intentional grounding in the end zone. That’s a lot of verbiage. So one step at a time:

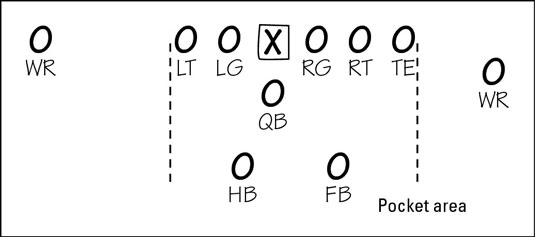

A safety is when an offensive player who has possession of the football is tackled in his own end zone. When this happens, the defense is awarded two points.

Intentional grounding happens when the quarterback is being pressured and chooses to get rid of the football (“throw it away”) rather than hold the football while being sacked. He would choose to do that because if he holds onto the football when he is sacked the ball will be spotted wherever the sack occurred, which is usually well behind the line of scrimmage and results in a lot of lost yardage for the offense. (For example, if the offense was originally lined up on the 30 yard line on 1st and 10 and the QB was sacked with the ball at the 20 yard line, the next down and distance would be 2nd and 20. It’s second down and the offense lost 10 yards on the previous play, so they now have 20 total yards to go to get a first down.) But if he throws it away in the vicinity of a receiver and it’s a catchable ball, it’s an incomplete pass and the ball goes back to the original line of scrimmage. (For example, if the offense was originally at the 30 yard line and the QB throws it away while under pressure, the next down and distance would be 2nd and 10 because it’s second down and the ball will be spotted at the original line of scrimmage, so the offense still has 10 yards to go to get a first down.)

However, if the quarterback throws the ball away “without a realistic chance of completion“ (a judgement call by the refs), he gets called for intentional grounding, which is a loss of down plus a ten yard penalty. (So, using our 1st and 10, 30 yard line example from above, the next play would be 2nd and 20: loss of down (from first down to second down) and a ten yard penalty (from 1st and 10 to 2nd and 20). If intentional grounding occurs in the end zone, it’s an automatic safety for the defense, a 2 point score.

That’s what happened to San Francisco yesterday.

Niners QB Colin Kaepernick was pressured in the end zone. He was being chased by multiple Rams defensive players and decided to throw the ball away instead of getting sacked in the end zone for a safety. However, in throwing it away to no one, he was called for intentional grounding, which also results in a safety.

And thus the Rams were awarded their first two points in the 13-13 tie that led to an overtime win. Tough break for a rookie QB.

Make sense?